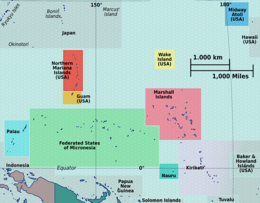

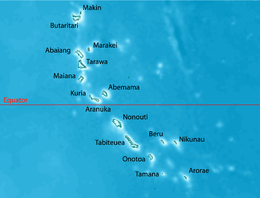

Butaritari is an atoll in the Pacific Ocean island nation of Kiribati. The atoll is roughly four-sided. The south and southeast portion of the atoll comprises a nearly continuous islet. The atoll reef is continuous but almost without islets along the north side. Bikati and Bikatieta islets occupy a corner of the reef at the extreme northwest tip of the atoll. Small islets are found on reef sections between channels on the west side. The lagoon of Butaritari is deep and can accommodate large ships, though the entrance passages are relatively narrow. It is the most fertile of the Gilbert Islands, with relatively good soils (for an atoll) and high rainfall. Butaritari atoll has a land area of 13.49 km2 (5.21 sq mi) and a population of 3,224 as of 2015[update]. During World War II, Butaritari was known by United States Armed Forces as Makin Atoll, and was the site of the Battle of Makin. Locally, Makin is the name of a separate but closest atoll, 3 kilometres (1.6 nmi; 1.9 mi) to the northeast of Butaritari, but close enough to be seen. These two atolls share a dialect of the Gilbertese language.

Map of Butaritari | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 3°10′04″N 172°49′33″E / 3.16778°N 172.82583°E |

| Archipelago | Gilbert Islands |

| Area | 13.49 km2 (5.21 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Largest village | Taubukinmeang |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 3,224 (2015 Census) |

| Pop. density | 322/km2 (834/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | I-Kiribati 90.6% |

Geography edit

Butaritari is the second most northerly of the Gilbert Islands; 3 kilometres (1.6 nmi; 1.9 mi) to the northeast is Makin. Butaritari was called Makin Atoll by the U.S. military, and present-day Makin was then known as Makin Meang (Northern Makin) or Little Makin to distinguish it. Now that Butaritari has become the preferred name for the larger atoll, speakers tend to drop the qualifier for Makin. Butaritari has also previously been known as Pitt Island, Taritari Island, or Touching Island.

The atoll is roughly four-sided and nearly 30 km (19 mi) across in the east–west direction, and averages about 15 km (9 mi) north to south. The reef is more submerged and broken into several broad channels along the west side. Small islets are found on reef sections between these channels. The atoll reef is continuous but almost without islets along the north side. In the northeast corner, the reef is some 1.75 km (1.09 mi) across and with only scattered small islet development. Thus, the lagoon of Butaritari is very open to exchange with the ocean. The lagoon is deep and can accommodate large ships, though the entrance passages are relatively narrow.[1]

The south and southeast portion of the atoll comprises a nearly continuous islet, broken only by a single, broad section of interislet reef. These islets are mostly between 0.2 km (0.1 mi) and 0.5 km (0.3 mi) across, but widen in the areas where the reef changes directions. Mangrove swamps appear well developed in these latter areas as well as all along the southern lagoon shore. (Narrow islets are somewhat characteristic of Kiribati atolls running east–west.)[1]

Bikati and Bikatieta islets occupy a corner of the reef at the extreme northwest tip of the atoll, bordering a small lagoon to the north of the main lagoon. There is a village on the larger Bikati (2 by 0.5 km).[1]

Environmental issues edit

Seepage of saltwater into the pits in which babai (Cyrtosperma merkusii or giant swamp taro) is grown is the major concern of islanders.[2] The erosion problems are identified as being linked to aggregate mining, land reclamation and the construction of causeways that is thought to change the currents along the shoreline.[2] The causeways have also resulted to reduced flushing of the lagoon that has resulted in low levels of oxygen, therefore causing damage to fish stocks in the lagoon and causes other biological problems.[2] Aggregate mining and the removal of coral boulders is exacerbating coastal erosion.[2]

Villages edit

The population of Butaritari in the 2010 Census[3] was 4,346 people, inhabiting twelve villages:

| Kuuma | 323 inhabitants |

| Ukiangang | 707 inhabitants |

| Bikaati | 225 inhabitants |

| Tikurere | 8 inhabitants |

| Keuea | 258 inhabitants |

| Tanimainiku | 248 inhabitants |

| Tanimaiaki | 267 inhabitants |

| Tabonuea | 271 inhabitants |

| Antekana | 217 inhabitants |

| Taubukinmeang | 835 inhabitants |

| Temanokunuea | 621 inhabitants |

| Onomaru | 366 inhabitants |

Climate edit

Butaritari is one of the lushest of the islands of Kiribati due to good rainfall. Typical annual rainfall is about 4 m, compared with about 2 m on Tarawa Atoll and 1 m in the far south of Kiribati. Rainfall on Butaritari is enhanced during an El Niño.

Economy edit

Butaritari has rich marine resources, with a large lagoon and wide reef. Butaritari has the greatest potential for agriculture in Kiribati: bananas, breadfruit and papaya grow well, and successful cultivars of pumpkin, cabbage, cucumber, eggplant and other vegetables have been created with assistance from the Taiwan Technical Mission based in South Tarawa. However, most households keep to a subsistence lifestyle and, although food is plentiful, money is often scarce as there are few paid jobs on the island.[4]

History edit

Early history edit

Myths and legends edit

There are different stories told as to the creation of Butaritari and the other islands in the Southern Gilberts. An important legend in the culture of Butaritari is that spirits who lived in a tree in Samoa migrated northward carrying branches from the tree, Te Kaintikuaba, which translates as the tree of life.[2] It was these spirits, together with Nareau the Wise who created the islands of Tungaru (the Gilbert Islands).[Note 1]

1606 to 1899 edit

The Spanish expedition led by Pedro Fernandes de Queirós sighted the Buen Viaje (good trip in Spanish) Islands (Butaritari and Makin) on 8 July 1606.[7][8]

Traditionally, Butaritari and Makin were ruled by a chief or Uea who lived on Butaritari Island.[2] This chief had all the powers and authority to make and impose decisions for Butaritari and Makin, a system very different from the southern Gilbert Islands where power was wielded collectively by the unimwane or old men.

The people of Kuma village had the power to call dolphins or whales, and used this ability on special occasions to provide meat for important feasts such as the opening of a new maneaba.[9]

The islands were visited as part of the United States Exploring Expedition in 1841.[10] Any possible Guano Islands Act claim by the United States to Butaritari and Little Makin was renounced in the 1970s.

The first traders resident in the Gilberts were Randell and Durant who arrived in 1846. Durant moved on the Makin, while Randell remained on Butaritari.[2] The earliest trading companies on Butaritari were the Hamburg-based Handels-und Plantagen-Gesellschaft der Südsee-Inseln zu Hamburg (DHPG) with Pacific headquarters in Samoa, and On Chong (Chinese traders with Australian connections via the goldfields). These traders helped Butaritari became the commercial and trading capital of the Gilbert Islands until Burns Philp, a powerful trading company, moved to Tarawa, following the seat of political power.

Robert Louis Stevenson, Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne visited Butaritari from 14 July 1889 to early August.[11] At this time Nakaeia was the ruler of Butaritari and Makin atolls, his father being Tebureimoa and his grandfather being Tetimararoa. Nakaeia was described by Stevenson as “a fellow of huge physical strength, masterful, violent … Alone in his islands it was he who dealt and profited; he was the planter and the merchant” with his subjects toiling in servitude and fear.[12]

Nakaeia allowed two San Francisco trading firms to operate, Messrs. Crawford and Messrs. Wightman Brothers, with up to 12 Europeans resident on islands of the atolls. The presence of the Europeans, and the alcohol they traded to the islanders, resulted in periodic alcoholic binges that only ended with Nakaeia making tapu (forbidding) the sale of alcohol. During the 15 or so days that Stevenson spent on Butaritari the islanders were engaged in a drunken spree that threatened the safety of Stevenson and his family. Stevenson adopted the strategy of describing himself as the son of Queen Victoria so as to ensure that he would be treated as a person who should not be threatened or harmed.[12]

The last Uea was Nauraura Nakoriri who was in power both before and after the Gilberts became a British Protectorate in 1892.[2]

1900 to 1941 edit

Butaritari Post Office opened on 1 January 1911.[13]

The Japanese trading company Nanyo Boeki Kabushiki Kaisha established operations in Butaritari Village. W. R. Carpenter & Co. (Solomon Islands) Ltd was established in 1922.[14][15][16] Through the 1920s On Chong experienced gradual decline in its operations as the result of low copra prices. Eventually On Chong was taken over by W. R. Carpenter & Co.

World War II edit

Japanese invasion edit

On 10 December 1941, three days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, 300 Japanese troops, plus laborers of the "Gilberts Invasion Special Landing Force" arrived off Butaritari — then known as "Makin" — and occupied without resistance. Lying east of the Marshall islands, Makin would make an excellent seaplane base, extending Japanese air patrols closer to Howland Island, Baker Island, Tuvalu, Phoenix and Ellice Islands, all held by the Allies and protecting the eastern flank of the Japanese perimeter from an Allied attack.

American raid edit

Butaritari atoll was the site of the Makin Raid in August 1942, when two companies of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion landed from the submarines USS Argonaut and USS Nautilus, as a feint to draw Japanese attention away from the planned invasion route through the Solomons. While they annihilated the local garrison, they failed in their initial objectives of taking prisoners and gathering intelligence.

American invasion edit

On the eve of invasion, the Japanese garrison consisted of 806 men. Most were of aviation or Japanese and Korean labor units who had little or no combat training and were not assigned weapons or a battle station. The number of trained combat troops on Makin was no more than 300 soldiers. The garrison included three tanks and three 37 mm (1.5 inch) anti-tank guns.

Butaritari's land defenses were centered around the lagoon shore, near the seaplane base in the central part of the island. A series of strongpoints was established along Butaritari's ocean side as the Japanese expected the invasion to come from there, following the example of a raid in 1942. Without aircraft, ships, or hope of reinforcement or relief, the outnumbered and outgunned defenders could only try to delay the American attack for as long as possible.

American air operations began on November 13, 1943, followed by bombardment from fire support ships. Troops began to go ashore on November 20, and the attacking troops knocked out the fortified strongpoints one by one. Despite their great superiority in men and weapons, the Americans had considerable difficulty subduing the island's small defensive force. On November 23 the force commander reported "Makin taken."

As compared to an estimated 395 Japanese and Koreans killed in action, American combat casualties numbered 66 killed and 152 wounded. But when the American losses incurred during the sinking of the escort carrier USS Liscome Bay on November 24 by a Japanese submarine are included, the loss balance tips toward the other side. Counting the 687 sailors who went down with the carrier, American casualties exceeded the strength of the entire Japanese garrison on Makin.

Visiting Butaritari edit

Butaritari is served by a twice weekly air service connecting with neighbouring Makin and the capital, South Tarawa, provided by Air Kiribati. The runway of Butaritari Atoll Airport was originally built as the World War II American strip (Starmann Field). An international air service with a route of Tarawa Atoll–Butaritari–Majuro operated for a short period in 1995. The aim was to facilitate the development of a strong cash crop economy on the island and link the Marshall Islands with Kiribati. With the demise of Air Nauru in 2008, the only international air connection is through South Tarawa, which is connected by a twice weekly Fiji Airways flight with Fiji.

There are three guesthouses on Butaritari, providing a basic level of accommodation aimed mainly at government staff and visitors, though tourists are welcomed.[17]

See also edit

- USS Makin Island: U.S. Navy for ships named for the island

- List of Guano Island claims

Notes edit

- ^ Sir Arthur Grimble, cadet administrative officer in the Gilberts from 1914 and resident commissioner of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony from 1926, recorded the myths and oral traditions of the Kiribati people. He wrote the best-sellers A Pattern of Islands (London, John Murray 1952,[5] and Return to the Islands (1957), which was republished by Eland, London in 2011, ISBN 978-1-906011-45-1. He also wrote Tungaru Traditions: writings on the atoll culture of the Gilbert Islands, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1989, ISBN 0-8248-1217-4.[6]

References edit

- ^ a b c "2. Butaritari" (PDF). Office of Te Beretitent - Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dr Temakei Tebano & others (September 2008). "Island/atoll climate change profiles - Butaritari Atoll". Office of Te Beretitent - Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series (for KAP II (Phase 2). Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ "Kiribati Census Report 2010 Volume 1" (PDF). National Statistics Office, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Government of Kiribati. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Butaritari Island Report". Government of Kiribati. Archived from the original on 2019-10-17. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- ^ Grimble, Arthur (1981). A Pattern of Islands. Penguin Travel Library. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-009517-9.

- ^ Grimble, Arthur (1989). Tungaru traditions: writings on the atoll culture of the Gilbert Islands. Penguin Travel Library. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1217-1.

- ^ Maude, H.E. (1959). "Spanish Discoveries in the Central Pacific: A Study in Identification". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 68 (4): 284–326.

- ^ Kelly, Celsus, O.F.M. La Austrialia del Espiritu Santo. The Journal of Fray Martín de Munilla O.F.M. and other documents relating to the Voyage of Pedro Fernández de Quirós to the South Sea (1605-1606) and the Franciscan Missionary Plan (1617-1627) Cambridge, 1966, p.39, 62.

- ^ "Visitor information, Butaritari" (PDF). Government of Kiribati.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Stanton, William (1975). The Great United States Exploring Expedition. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 245. ISBN 0520025571.

- ^ Osborne, Ernest (20 September 1933). "Stevenson's Bouse on Butaritari". IV(2) Pacific Islands Monthly. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ a b In the South Seas (1896) & (1900) Chatto & Windus; republished by The Hogarth Press (1987), Part IV

- ^ Premier Postal History. "Post Office List". Premier Postal Auctions. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ WR Carpenter (PNG) Group of Companies: About Us, http://www.carpenters.com.pg/wrc/aboutus.html Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 12 Dec 2011.

- ^ Deryck Scarr: Fiji, A Short History, George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd., Hemel Hempstead, Herts, England, p. 122.

- ^ MBf Holdings Berhad: About Us, http://www.mbfh.com.my/aboutus.htm Archived 2017-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 12 Dec 2011.

- ^ "Outer Islands Accommodation Guide". Kiribati Tourism, Government of Kiribati. Archived from the original on 2014-07-18. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

External links edit

- Exhibit: The Alfred Agate Collection: The United States Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842 from the Navy Art Gallery

- Stevenson, Robert L. (1896), In the South Seas

- http://www.janeresture.com/butaritari/index.htm - Republic

- http://www.factmonster.com/ce6/world/A0809615.html - Facts

- https://web.archive.org/web/20081227093332/http://www.pacificislandtravel.com/kiribati/about_destin/butaritari.html - Main Info