Paradise Airlines Flight 901A

.jpg/290px-Lockheed_049_N9414H_(5854499965).jpg) A Lockheed Constellation, similar to the one involved in the accident. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | March 1, 1964 |

| Summary | Pilot error due to low visibility. |

| Site | Genoa Peak, Nevada, U.S. (east of Lake Tahoe) 39°00′59″N 119°53′20″W / 39.0163°N 119.8888°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Lockheed L-049 Constellation |

| Operator | Paradise Airlines |

| Registration | N86504 |

| Flight origin | Oakland International Airport |

| 1st stopover | Salinas Airport |

| 2nd stopover | San Jose Airport |

| Destination | Tahoe Valley Airport |

| Passengers | 81 |

| Crew | 4 |

| Fatalities | 85 |

| Survivors | 0 |

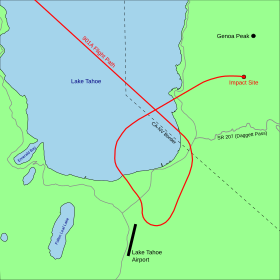

Paradise Airlines Flight 901A was a scheduled passenger flight from San Jose Municipal Airport to Tahoe Valley Airport, both within California, USA. On March 1, 1964, the Lockheed L-049 Constellation serving the flight crashed near Genoa Peak, on the eastern side of Lake Tahoe during a heavy snowstorm, killing all 85 aboard. After the crash site was located, the recovery of the wreckage and the bodies of the victims took most of a month. Crash investigators concluded that the primary cause of the accident was the pilot's decision to attempt to land at Tahoe Valley Airport when the visibility was too low due to clouds and snowstorms in the area. After aborting the landing attempt, the flight crew lost awareness of the plane's location as it flew below the minimum safe altitude in mountainous terrain. The pilot likely tried to fly through a low mountain pass in an attempt to divert to the airport in Reno, Nevada, and crashed into the left shoulder of the pass. At the time, it was the second-deadliest single-plane crash in United States history, and remains the worst accident involving the Lockheed L-049 Constellation.

The airline involved was a two-year-old company that operated discount excursion flights from the San Francisco Bay Area to Lake Tahoe. After the accident, investigators from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) uncovered multiple safety violations by the company and grounded all of its flights. After an unsuccessful appeal by the company, the FAA revoked its operating certificate and Paradise Airlines permanently shut down.

Accident[edit]

Flight 901A was one of two daily passenger flights operated by Paradise Airlines between San Jose Municipal Airport and Tahoe Valley Airport.[1] On the morning of Sunday, March 1, 1964, the Lockheed L-049 Constellation operating the flight took off from the company's base at Oakland International Airport with only the four crew members aboard, and made a pre-arranged stop at nearby Salinas Airport to pick up a group of eighteen passengers before proceeding to San Jose Airport, where more passengers were waiting.[2][3] There was only space for 63 of the waiting passengers; the remaining 15 travelers were unable to board because the aircraft was filled to capacity. The airline shuttled them by bus to Oakland to catch a later flight. The aircraft, with 81 passengers and 4 crew members, departed San Jose at 10:39 a.m. PST for the 50-minute flight to Lake Tahoe. The passengers who had been bussed to Oakland eventually learned that the later flight was canceled due to poor weather in the mountains.[4] Though the U.S. Weather Bureau forecast for the Lake Tahoe region predicted weather conditions that would have been unsuitable for flights, the Paradise Airlines dispatcher estimated that by Flight 901A's scheduled arrival time, weather conditions would have improved, so he approved the aircraft's departure.[5]: 2 En route, the crew of Flight 901A spoke by radio to the company's other plane, which had just left the Tahoe Airport on its way to Oakland. That crew said that they had encountered icing conditions at 12,000 feet (3,700 m), snow showers over Lake Tahoe, and that clouds had obscured the tops of mountains in the vicinity.[5]: 4 At 11:21 a.m., the pilot of Flight 901A, near Lake Tahoe, reported to the Oakland air route traffic control center that he had spotted a break in the cloud cover, that he could see the airport on the south shore of the lake, and that he was going to proceed with a visual approach.[5]: 5 [4][6] At 11:27 a.m., the pilots contacted the passenger agent for Paradise Airlines at Tahoe Valley Airport to let him know they would be arriving shortly and that he should be prepared for the incoming passengers. The agent informed them that the 11:00 a.m. Weather Bureau report described the weather conditions as overcast, 2,000 feet (610 m) estimated ceiling, with 3 miles (5 km) visibility.[5]: 5 According to Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations for the airport, the weather report had to have a minimum ceiling of 4,000 feet (1,200 m) and 10 miles (16 km) visibility before a commercial passenger aircraft could attempt an approach, so the incoming flight could not be given permission to land.[7]

There were different witnesses who testified either seeing or hearing the aircraft at different points in its flight near South Lake Tahoe. Investigators concluded that the flight flew south across the lake at an altitude of about 500 feet (150 m) toward the airport on the south end. According to the witnesses, it was not showing any obvious mechanical problems. Near the airport, the plane entered an area of cloud cover, then added power to the engines and turned back north towards the lake. It then turned to the east and flew away from the lake. By this time the weather conditions had deteriorated into blizzard conditions, and witnesses could only hear the plane engines, which abruptly stopped. The witnesses did not hear the sound of an explosion or crash.[5]: 6–7

The aircraft struck the ground at the crest of a ridge near Genoa Peak, Nevada. That section of the mountains around the lake, with a maximum height of 8,900 feet (2,700 m) above sea level, forms the north shoulder of Daggett Pass, a pass several miles across which has an average elevation of 7,300 feet (2,200 m) above sea level.[5]: 7 Just before impact, the plane struck several of the trees on the ridge's west slope, and the pattern of damage to the trees showed that the aircraft was flying almost level at the time.[5]: 8 The crash occurred just 25 to 30 feet (8 to 9 m) below the top of the ridge, leaving a trail of wreckage approximately 900 feet (270 m) long.[6] If the aircraft had been 100 feet (30 m) more to the right at the altitude it was flying, it would have cleared the ridge.[7]

Paradise Airlines had been operating as an intrastate airline in California for about two years, and had not had any accidents in its history before this flight.[8][9] It is the deadliest accident involving the Lockheed L-049 Constellation,[10] and at the time was the second deadliest single-plane accident in United States history, exceeded only by American Airlines Flight 1 two years earlier.[4][11]

Aftermath[edit]

.jpg/220px-South_Lake_Tahoe%2C_Nevada_(21572265225).jpg)

When the aircraft was determined to be missing, search efforts commenced, but because of the heavy snowstorms in the Tahoe area, efforts were severely limited on the first day. Two small boats searched along a ten-mile (16 km) stretch of the lake's shore, but by nightfall, the searchers had found no trace of the missing aircraft. Experienced ski rescue crews and mountaineers waited for a break in the weather before they could join the search.[4] By dawn the next morning, the weather had cleared enough to permit a large-scale search.[12] Air Force Lt. Col. Alexander Sherry headed the operation, involving more than fifty planes and hundreds of people.[9] At 7:36 a.m., an Air Force helicopter spotted the wreckage of the aircraft on the ridge. A second helicopter landed at the site and confirmed that the wreckage was from the missing flight. It also confirmed that there were no survivors.[12] Looters had already been to the site and stolen cash and jewelry from the crash victims.[13]

Douglas County Sheriff's deputies led a group of off-road vehicles to the crash scene and left two deputies there overnight to guard the wreckage.[2] A bulldozer cleared a 3+1⁄2-mile (6 km) road to the site along an old logging track to make it easier for rescuers and investigators to reach it.[2][14] Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) investigators arrived at the scene of the crash and began to sift through the wreckage of the aircraft for clues as to why it crashed.[2] Most of the wreckage they found was shattered into tiny pieces, with only a few recognizable parts.[15] Portions of the four engines had burned, and there was evidence that a small area of the crash site had burned for four or five hours. The impact site was so close to the top of the ridge that the wheel from the aircraft's nose gear was found on the other side of the mountain.[6]

Rescuers estimated that because of the rugged terrain and the deep snow, it would take several days or possibly even months until after the spring thaw before all the victims could be recovered.[2] The first seven were brought to a makeshift morgue in the CVIC Hall in Minden, Nevada, on March 3, two days after the crash, where technicians from the Federal Bureau of Investigation began the process of identification.[14] An additional 43 victims were brought the next day, with officials hurrying to recover bodies before an incoming snowstorm buried them in the snow, making them even harder to locate.[16] The Air Force flew in a helicopter to help shuttle the bodies down from the ridge.[17] Two large Army helicopters brought in three 600-pound (270 kg) mobile hot air furnaces to the site to help melt away the snow.[18] By March 6, searchers had located and recovered all but two of the victims.[19] The last two were eventually located, but by March 9, officials had only been able to recover one of them before poor weather forced them to halt recovery operations.[20] The final victim was removed from the site on March 30, about a month after the crash.[21] Douglas County district attorney John Chrislaw reported that Paradise Airlines refused to pay the $300 (equivalent to $2,800 in 2022[22]) per victim mortuary expenses of handling the remains, leaving the victims' relatives to bear the cost.[16] Paradise Airlines president Herman Jones denied the report, saying that the expenses would be paid by the airline's insurance company.[23]

Airline grounded[edit]

After cancelling flights immediately after the crash, Paradise Airlines resumed flights to Lake Tahoe on the morning of March 3, two days after the accident.[25] The FAA immediately ordered an emergency suspension of all flights by the airline, which took effect at noon on March 4. The suspension order said that the airline had shown "a lack of ability and qualifications to conduct a safe intrastate common carrier passenger operation". The agency said that the airline could appeal the suspension, but that in the meantime, it could not conduct flights until a decision was made on the appeal.[18] FAA Regional Director Joseph Tippets said the agency was being so strict with the airline because Flight 901A had been dispatched on its fatal flight at a time when the weather conditions at the destination airport would not have permitted a safe landing. He said that the same day, the airline had also allowed its other aircraft to take off from Tahoe Valley Airport when the local weather conditions prohibited it. Both planes had been flying in conditions where icing would have been likely, but neither of them were equipped with wing de-icing equipment.[26][27] Instead, the front edges of the wings of the two aircraft had simply been painted black, which made it look like they had de-icing equipment installed.[28]

Company president Herman Jones told reporters that he was puzzled by the FAA's action, saying that to his knowledge, the agency had found no problems with the company's operation or its paperwork.[29] In the days following the suspension, he added that he believed that the FAA's "over-restrictive rules" about flying in adverse weather conditions were to blame for the accident. According to him, the aircraft was only three or four miles from the Tahoe Airport by the time the Tahoe Airport agent told them that the weather report stated that there was only a 2,000-foot (610 m) ceiling. Jones said the pilots may have already had the airport in sight, but instead of landing safely, the pilot probably decided to fly over to Reno in order to avoid being cited by the FAA for landing in violation of the airport weather minimums.[7]

At the outset of the appeal hearing before the FAA, Paradise Airlines tried to argue that the agency had no jurisdiction over the company because it was an intrastate airline that normally operated only within state boundaries.[30] The company was unsuccessful making that argument. Once testimony commenced, attention was first focused on the company dispatcher who had approved the flight despite the poor weather conditions. At 25 years old, he was very inexperienced and had been employed by the company for only one month. He was not very fluent with the English language, and in response to questioning by the FAA, was unable to provide explanations of crucial weather terms that appeared in that day's forecast.[31] He testified that he had used his own judgment and predicted that weather conditions at Tahoe Airport would be safe enough for the flight to land by the time it arrived. However, when he was given several examples of different weather conditions during the hearing, he was unable to accurately describe how those weather conditions could affect flight safety.[32]

Later in the hearing, FAA investigators revealed that Raymond Rickard, the Tahoe Valley operations manager for Paradise Airlines, had made changes to notes made by the airport's official weather observer on the morning of the flight. Rickard testified that he had written a minus sign in front of a certain meteorological symbol on the report, which changed its meaning from "broken cloud ceiling" to "thin, broken clouds". He said, "I knew [the observer] would not let us dispatch an airplane under the conditions he'd written, so I just inserted the minus sign."[33] He said he did this because he had heard the observer tell another pilot that it was all right to take off, so he thought that the observer had just made a mistake on the report. However, the observer testified that he was positive that he had seen weather conditions well below minimum operating conditions that morning.[34] Another FAA investigator testified that Paradise Airlines had violated civil air regulations several times in the three months before the accident, mostly involving weather conditions.[35]

On April 6, the company lost its appeal of the FAA order grounding the company's aircraft.[36] Paradise Airlines president Herman Jones called the hearings "a great miscarriage of justice" and vowed to keep the company's planes flying, with or without an air operator's certificate.[37] FAA representatives countered that if the company attempted to fly without a certificate, the United States Marshals Service would seize the aircraft involved.[38] After the ruling, the airline shut down.[39]

Aircraft[edit]

The aircraft was a Lockheed L-049 Constellation, serial number 2025 and registered with tail number N86504. Assembly of the aircraft finished in December 1945, and at the time of the crash it been operated for 45,629 hours.[5]: 25 It was equipped with four Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone propeller engines that had undergone a total overhaul within the past 1,300 flight hours.[5]: 26

The plane was owned by Nevada Airmotive Corporation of Las Vegas, and had been leased to Paradise Airlines since June 1963.[36] It had been previously owned and operated by Trans World Airlines.[3] Paradise Airlines had flown it a total of 551 hours.[5]: 25 According to the FAA, the type of aircraft was well suited for operation in high-altitude, mountainous airports like Lake Tahoe, due to its relatively slow speed and high maneuverability.[40]

Passengers and crew[edit]

Paradise Airlines Flight 901A carried 81 passengers and 4 crew on its final flight.[4] Nearly all of the passengers were from the Salinas and San Jose areas.[6] All but two of the eighteen passengers that the airline had picked up at its Salinas stop were employees of the Monte Mar Development company of Salinas and Monterey.[4]

The captain of the flight was Henry Norris, age 45, who had been employed with the airline since November 1963.[5]: 24 [41] He had 15,391 hours of flight time, including 3,266 hours in Lockheed Constellation type aircraft.[5]: 24 He had served in the Air Transport Command during World War II, had flown as a pilot for Modern Air Transport and World Airways, and served as the director of training for Alaska Airlines.[41][42] He was unmarried and a resident of Alameda, California.[9][41]

The first officer, 28-year-old Donald A. Watson, of San Francisco, had been employed with the company since March 1963.[5]: 24 [9] He had 3,553 flight hours of experience, including 149 hours instrument time and 1,353 hours in the Lockheed Constellation.[5]: 24 Before joining Paradise Airlines, he had served as a mechanic with Pan American Airways and a pilot with Flying Tiger Line.[41]

The flight engineer, Jack C. Worthley, 33, of Fremont, California, had been employed with the company since October 1963.[5]: 25 [9] He had 3,700 flight hours as a flight engineer, including 912 hours on the Lockheed Constellation.[5]: 25 He was the father of three children and was a native of Seattle.[41]

Investigation[edit]

Investigators from the CAB arrived at the headquarters of Paradise Airlines on the day the plane went missing, even before the crash site had been located. Just as company president Herman Jones was about to meet with officials from the CAB and the FAA the next morning, word came in that the crash site had been located.[9] After the meeting, investigators impounded all of the company's records.[6] More than thirty CAB investigators were involved in the probe, studying the maintenance records of the plane, interviewing witnesses, studying the weather reports, and examining pieces of the wreckage for indications of the cause of the crash. The aircraft was not equipped with a cockpit voice recorder.[43] All four propeller hub assemblies were located and shipped, with the broken propeller blades, to a shop in Hayward, California, to determine how much power the engines were generating when the plane crashed.[19] By May 1, investigators had recovered the key instruments and the radio equipment of the crashed plane. A salvage operator began removing the rest of the plane, taking the pieces to a warehouse at Reid–Hillview Airport near San Jose and storing them there in case they were needed by CAB investigators.[39]

The CAB held a probable cause hearing in Oakland from June 2–5. The investigative team learned that pilots had made eleven reports of problems with the plane's directional instruments in the nine months before the crash.[44][5]: 9 Testimony from the Tahoe Airport's weather observer repeated some of what was said during the appeal of the FAA's suspension of Paradise Airlines' operating certificate.[44] The pilot of the Paradise Airlines flight that left Lake Tahoe an hour before the crash testified that he took off because the weather observer assured him that the weather was clear enough, but the observer said that he did not recall such a conversation. The pilot was asked about the company's procedures for operating in bad weather, and the company's financial arrangements with its pilots. He explained that the pilots were paid a flat fee of $35 (equivalent to $300 in 2022[22]) per flight. In the hearing, the CAB interviewer hinted that the financial arrangements gave an incentive to pilots to avoid diversions due to bad weather because they would not be paid for their additional time.[45]

Investigators learned that neither of the company's aircraft operating at the Tahoe Airport had been equipped with de-icing equipment, and that Flight 802 had picked up rime ice half an inch thick when it was flying out of the Tahoe Valley earlier that day. They also learned that the maintenance records of the company's aircraft had several discrepancies, but that the FAA had no enforcement actions pending at the time of the crash. Previous flight crews had noted minor errors in the altimeters aboard the aircraft, and instrument repairmen had worked on both altimeters in the plane that crashed in the incident. The first officer's fluxgate compass was known to be faulty on the day of the crash, with crews reporting that it was "completely unreliable in any kind of banking turn". Instrument technicians had worked on it two days earlier, but it was still not functioning reliably. Investigators learned that there had been gaps in the cloud cover when the flight had arrived, but a snow squall hit the north end of the airport just as the aircraft was approaching from the north for landing.[27]

On July 15, 1965, the CAB released its final report. The report stated that the crash was caused by pilot error, a falsified weather report, and illegal maintenance practices.[46] The accident report stated:[5]: 1

The Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the pilot's deviation from prescribed VFR flight procedures in attempting a visual landing approach in adverse weather conditions. This resulted in an abandoned approach and geographical disorientation while flying below the minimum altitude prescribed for operations in mountainous areas.

The CAB report stated that maintenance had been performed on both altimeters and the No. 2 fluxgate compass transmitter on the evening before the accident.[5]: 9 Paradise Airlines did not have any of its own maintenance personnel, and used an FAA-approved maintenance company located at Oakland Airport.[47] The technicians who had performed the work had also inspected and signed off on their own work.[5]: 9, 18 The report stated the mechanic who had worked on the compass had never worked on that type of transmitter, and did not refer to any technical publications for guidance.[5]: 9–10 He failed to check the entire system and did not perform all of the actions outlined in the maintenance manual. The technician who performed the work on the altimeters could not remember whether or not he had secured the barometric adjusting screw that he had unscrewed during the adjustments he had made. The reinstallation of the unit had been performed by a mechanic who had never performed that type of work before, and had been done without performing all of the checks outlined in the manual.[5]: 10 The captain's altimeter that was recovered from the wreckage showed a pre-impact discrepancy that would have indicated the aircraft was flying 280 feet (85 m) higher than its true altitude.[5]: 17 In addition, the compass had an error of 15 degrees or more, which at the moment of the crash could have caused the aircraft's indicated heading to be more southerly than the aircraft's true heading.[5]: 18

Weather reports that were available to the company dispatcher included warnings of icing conditions in the Tahoe Airport area and that clouds and snow showers would be obscuring the mountains in western Nevada.[5]: 12 None of this information was communicated to the captain of Flight 901A before or during the flight, and the board speculated that ice accumulation on the aircraft may have affected its ability to gain sufficient altitude to clear the mountains while attempting to divert.[5]: 13, 20

The report concluded that when the crew abandoned the approach to Tahoe Valley Airport, they decided to proceed through Daggett Pass for unknown reasons, possibly to avoid an area of known icing that they had passed through during their descent, or possibly because icing was preventing the aircraft from being able to climb higher.[5]: 20 The pilots would have been aware that an altitude of 9,000 feet (2,700 m) would have given the aircraft 1,500 feet (460 m) of terrain clearance through the pass's center, and an easterly heading from the southern end of the lake would have taken the aircraft through the pass's center, an opening several miles wide. The aircraft leveled off at 9,000 feet, either because the pilots believed that they had sufficient clearance, or because icing prevented further altitude gains.[5]: 19 It was possible that the crew was unaware that its heading, altitude, or both, were not being accurately shown on the aircraft's instruments, and that undetected tail winds might also have affected the flight's heading.[5]: 21

References[edit]

- ^ "Paradise Lines Launched Just Two Years Ago". Salinas Californian. Salinas, California. UPI. March 3, 1964. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e "Snow Delays Air Crash Probe". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. March 3, 1964. pp. 1, 3. Archived from the original on June 14, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Airline Cut Rate Operator". The San Francisco Examiner. March 2, 1964. p. 15. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "85 on Lost Tahoe Plane". The San Francisco Examiner. March 2, 1964. pp. 1, 15. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "Aircraft Accident Report: Paradise Airlines, Inc. Lockheed Constellation, L-049, N 86504 near Zephyr Cove, Nevada, March 1, 1964" (PDF). Civil Aeronautics Board. July 15, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019. See copy at the National Transportation Library Archived July 5, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e O'Brien, William (March 3, 1964). "Mountain of Death; Crash Eyewitness". The San Francisco Examiner. pp. 1, 6. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Eaton, Bill (March 8, 1964). "Stiff Rules Blamed for Air Crash". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. pp. 1, 8. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Airline Certified for Lake Service". Reno Gazette-Journal. December 19, 1962. p. 13. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "Probe Before Air Wreckage Found". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. March 2, 1964. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Lockheed L-049 Constellation N86504 Lake Tahoe Airport, CA (TVL)". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on June 10, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ "Crash 2nd Worst in U.S. History". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. March 2, 1964. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "85 on Lost Plane Are Found Dead". The New York Times. UPI. March 3, 1964. p. 71. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ Nordstrand, Dave (August 20, 2014). "Resident recalls plane crash that killed his parents". Salinas Californian. Salinas, California. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "First Bodies Brought From Death Peak". The San Francisco Examiner. March 4, 1964. p. 22. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ O'Brien, William (March 3, 1964). "Bodies in Snow–An Eyewitness". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 7. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Next-of-kin Must Bear Cost of Recovering Bodies of Crash Victims". Reno Gazette-Journal. Reno, Nevada. March 5, 1964. pp. 1, 8. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tighter Plane Control Urged". The San Francisco Examiner. March 6, 1964. p. 17. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Tahoe Line Planes All Grounded". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. March 4, 1964. pp. 1, 5. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Bodies of Two Still Missing". Reno Gazette-Journal. Reno, Nevada. March 7, 1964. p. 9. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tahoe-- All 85 Air Victims Identified". The San Francisco Examiner. March 9, 1964. p. 11. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bias in Tahoe Probe Charged". The San Francisco Examiner. March 31, 1964. p. 6. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Mortician Defends $300 Price". Reno Gazette-Journal. Reno, Nevada. March 7, 1964. p. 9. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Pilot Guide: Flight in Icing Conditions (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration (Report). October 8, 2015. p. 19. AC 91-74B. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 17, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ "Paradise Back in the Air". The San Francisco Examiner. March 4, 1964. p. 22. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Paradise Airlines Grounded". Salinas Californian. Salinas, California. UPI. March 4, 1964. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Eaton, Bill (June 6, 1964). "Air Crash Cause Remains Mystery". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. p. 2. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "61 Damage Suits in Tahoe Crash Settled". The Californian. Salinas, California. December 20, 1966. pp. 1, 2. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "FAA Grounds Tahoe Crash Airline". The San Francisco Examiner. March 5, 1964. p. 5. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "CAB Rebuffs Paradise Air Lines". The San Francisco Examiner. March 21, 1964. p. 18. Archived from the original on June 14, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Inexperienced Hand Sent Fatal Tahoe Flight Aloft". The San Francisco Examiner. March 26, 1964. p. 16. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Uneasy Seat for Witness". The San Francisco Examiner. April 2, 1964. p. 9. Archived from the original on June 14, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ludlow, Lynn (March 27, 1964). "Forecast in Air Crash 'Altered'". The San Francisco Examiner. pp. 1, 10. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Forecast Factor in Airline Disaster". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. March 27, 1964. p. 16. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Paradise Lines' 'Other Violations'". The San Francisco Examiner. April 4, 1964. p. 8. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Hearing May Seal Death of Airline". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. April 23, 1964. p. 16. Archived from the original on June 14, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Threat by Paradise Airlines". The San Francisco Examiner. April 8, 1964. p. 10. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Paradise Planes Face U.S. Seizure". The San Francisco Examiner. April 11, 1964. p. 10. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Plane's Remains Scoured for Clues". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. May 2, 1964. p. 8. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jordan, Rich (March 3, 1964). "Little Supervision Needed – Who Kept Eye on Tahoe Runs?". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 6. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e "Passenger List on Airliner". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. March 2, 1964. pp. 1, 4. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fallon Pilot's Plane Feared Down in Pacific". Reno Gazette-Journal. Reno, Nevada. March 28, 1964. pp. 1, 5. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Probers Gather at Crash Site". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, California. March 3, 1964. p. 3. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Jordan, Rich (June 3, 1964). "Paradise Pilot Flunked". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 7. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jordan, Rich (June 4, 1964). "Fogginess on the Weather". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 3. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Pilots Blamed in Death of 85". The San Francisco Examiner. July 16, 1965. p. 9. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Aviation: Flight 901A..." Time. July 20, 1965. Archived from the original on April 14, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States in 1964

- Accidents and incidents involving the Lockheed Constellation

- Airliner accidents and incidents in Nevada

- 1964 in Nevada

- March 1964 events in the United States

- Airliner accidents and incidents caused by pilot error

- Accidents and incidents by airline of the United States