The Incredible Military Career of Lucien Stervinou

By Jeff Goodson

There’s a forested canyon above the town of Quimper in northwest France called les Gorge du Stangala. Drained by the Odet river, it’s known locally for its wild beauty and tranquility. In World War II, while training with the British Special Air Service in Scotland, the name was adopted as the nom de guerre of a French resistance fighter and special operations warrior named Lucien Stervinou.

Over the course of six years, from 1940-1946, Stervinou fought behind enemy lines in Europe and Indochina. He earned both the Croix de Guerre and France’s highest military award, the Legion d’Honneur. His story is the story of western special operations at the dawn of the modern age of irregular warfare.

Escaping the Nazis

Lucien Corentin Stervinou was born in Langalet, France (Brittany) in 1923. He was barely 17 when he first set out to escape the Nazis. As a German Panzer division moved toward the French port of Brest, he and his grandmother heard a radio appeal from Brigadier General Charles De Gaulle in London: “Frenchmen, we have lost a battle; we have not lost the war. From wherever you are, come join me and continue the fight.” It was June 18, 1940, just four days before Marshall Petain signed the Armistice with Germany.

Young Stervinou hopped on his bicycle, peddled the two miles to Chateauneuf du Faou, and met up with three of his soccer buddies. The four of them drove south to the port of Concarneau, and talked the captain of a Norwegian fishing boat into taking them aboard along with a group of French troops that he was surreptitiously evacuating to England. The seas became extremely rough, and half-way across the English Channel the captain turned about and returned to La Rochelle.

A few hours before the Nazis arrived, Stervinou jumped a military train for Bordeaux. He then went to Marseilles, Lyon and Vichy, before working his way to Quimper where he settled in with a resistance group that a young priest introduced him to.

When the Quimper group was later discovered, Stervinou fled to Paris and hid out in the apartment of famous resistance fighter Yves Allain. Allain, who was later murdered in Morocco, ran the Bourgogne escape route through which some 250 allied airmen escaped Nazi capture by crossing the Pyrenees into Spain. In June 1942 Stervinou followed that route with Allain, two British pilots and a small group of civilians, crossing the Pyrenees near Pau at night with a Basque guide.

After splitting up in Spain, Stervinou was captured by Spanish border guards and jailed in Jaca, Huesca and Saragossa. A few weeks later, he was ransomed to the British Consul, who organized his travel through Madrid and Gibralter to a British air base near Swindon, England. He arrived July 28, 1942, just over two years after his first attempt to escape the Nazis.

Supporting the French Resistance

Stervinou’s first stop was “Patriotic School” near Wimbledon, where all foreigners entering England were held and interrogated at length. He was then released to the Free French Forces, who he worked with for the rest of the war.

After five months of basic training at Camp Rake Manor in Surrey, Stervinou was recruited by France’s Central Bureau of Intelligence and Operations (BCRA). Similar to the OSS, but smaller, BCRA was the precursor of France’s External Documentation and Counter-Espionage Service (SDECE)—today known as the Directorate General for External Security (DGSE).

Stervinou trained at the British Army Commando Training Center, the BCRA training Center, and the Parachute Center at Ringway. While training with the British Special Air Service (SAS) near Iveranay, Scotland, he took the nom de guerre Stangala. From then through the first half of 1944, he worked communications between London and various French resistance groups.

D-Day and Return to Paris

In late May 1944, three “sticks” of ten men each were flown to an unnamed base in the south of England where they were separated from other units. Just before D-Day, on June 4, 1944, Stervinou’s stick was parachuted into an area prepared by a local resistance group west of Vire in Normandy. They brought arms and equipment, and trained the resistance fighters who met them in the use of heavy armaments, communications and fighting tactics. Other sticks parachuted that night into Brittany to destroy railroads and bridges.

For two months after D-Day, while operating behind enemy lines, Stervinou’s stick avoided German soldiers and the French milice who fought with them. Finally, in August they were ordered to Paris to regroup and help maintain security in the center of the city. On August 26, 1944, while providing protection from a rooftop, he watched General Charles De Gaulle march in triumph down the Champs Elysee. It was the end of Stervinou’s military service in the European theater.

Indochina and Force 136

With dissolution of the French resistance groups, focus shifted to the Pacific theater where the objective was establishing a French military presence and returning Indochina to the colonial field. Stervinou left Paris in January 1945 for Cairo. He then took a “flying boat” to Karachi, Bombay and Calcutta, where he again was trained by the British. This time it was Force 136, at their commando training center for the South Pacific Theater, where he trained for six months in parachuting, radio communications and jungle warfare.

Force 136 in Calcutta in 1945. The pass uses his nom de guerre, “Stangala”,

the name of a forested canyon near Quimper, France.

Today, few Americans have heard of Force 136. The British Special Operations Executive (SOE) was established in 1940 at the same time that the British Commandos were formed at the request of Winston Churchill. The SOE carried out sabotage and subversive operations in Europe, and its success led to a knockoff called “The Oriental Mission” in Burma. Codenamed Force 136, branches were soon established in Burma, Siam, Malaya and Indochina where they supported resistance movements in enemy-occupied territory and conducted sabotage operations. Rolled up in 1946, Force 136 was one of the first modern organizations to systematically operationalize what today we call unconventional warfare.

At the end of training, Stervinou’s group was reviewed by Lord Mountbatten, Viceroy of India, after which he took a DC-3 “over the hump” from Bajshahi Airbase to Kunming, China. Others were dropped in Laos, where they ultimately met severe losses and had only limited success.

“The Kunming commando groups were deployed on the Sino-Indochinese frontier in preparation for the Chinese invasion of Indochina in 1945. I parachuted into Pakhoi, a Chinese port in Kuang-tong Province. I was an intelligence officer with the French Navy, patrolling the Along Bay in northern Vietnam.”

The Weichow Raid

Stervinou’s unit operated closely with elements of the OSS, and he was part of a joint OSS/French commando attack on July 22, 1945 that knocked out an advance Japanese airbase on the island of Ouai-Tchao (Weichow).

“A joint Franco/American commando unit landed on the island at 2 AM, and the air base defense was quickly overpowered. Using the newly acquired TNT explosive, the tower and the landing lanes were rendered unusable. Now my earlier explosive training made sense.”

The mission was important, and both Kunming and General Chenault, Commander of the 14th Air Force, were notified of its success.

The Japanese Surrender of Vietnam

After the Weichow raid, Stervinou’s PT boat Crayssac returned to operating among the islands of Along Bay.

“Our nomadic life continued, stopping, controlling and often seizing equipment and foodstuff destined to the Japanese army by commercial junks. We created additional bases on the islands of Gow-To, Table and Singe.

A few short weeks later, the U.S. dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima (August 6th) and Nagasaki (August 9th). The bombing had the desired effect, and Hirohito announced the Japanese surrender on August 15th.

The next day, the five men of the Crayssac were ordered to Haiphong Bay to receive the surrender of the 60,000 Japanese soldiers then in Vietnam. They arrived at 4 PM.

“The Japanese authorities seemed astounded by our arrival. On the 16th, Japanese Colonel Kamya arrived during the night to inform us that General Tsushihashi, Japanese commander of north Indochina, had not received the order to surrender from Tokyo and for us to remain on board ship. He received his order the following morning.”

For several days after surrendering, the Japanese supplied the Crayssac crew with food and water. They then provided them an escort to Hanoi, where they arrived August 23rd and joined a handful of French administrators under Major Jean Sainteny and a small group of OSS personnel.

Eleven Men

Years later, Stervinou wrote that:

‘The political scene was chaotic…On August 23rd, we found ourselves, eleven men, in the former Governor General’s palace with responsibility for overseeing the security of 30,000 French civilians. It could only be done by negotiations with the new government of the Viet-Minh, the Japanese army responsible for maintaining security, and later the Chinese army. We had responsibilities beyond our ranks and experience.

‘Twice, I accompanied my commanding officer to meet Ho Chi Minh. I also met, and for a time worked in liaison with another Vietnamese leader on security matters, Vo Nguyen Giap. At the time, the French did not know whether these two men were nationalist leaders or communist ideologues. Later, Giap was the mastermind of the final and decisive battle that ended France’s colonial domination of Viet-Nam, Dien Bien Phu.

‘It wasn’t obvious to us then, but we had in front of us the beginning of the crumbling colonial era.’

Kidnapped, the Last Firefight and Demobilization

Months later, while investigating the conditions of French ex-POWs in the area, Stervinou was kidnapped in Vinh and spirited away for purposes unknown. He was only released when an American Air Ground Air Service major threated local authorities with a U.S. paratrooper attack.

Back in Hanoi, Stervinou contracted amoebic dysentery and was evacuated to Saigon. After five weeks recovering in the hospital, he was sent back to Along Bay on a destroyer to again serve as intelligence officer. His final kinetic engagement was on March 6, 1946, in a sustained firefight with Chinese forces in the port of Haiphong.

Shortly after, Stervinou fell to a recurring attack of dysentery and was evacuated to Saigon. After three more weeks in the hospital, he returned to France on a transport ship where he was demobilized and, on September 17, 1946, finally discharged. For him, the wars were over.

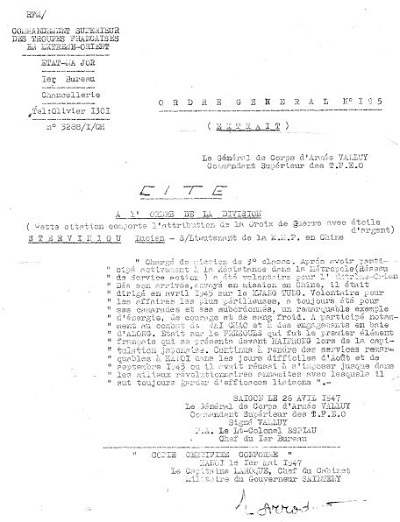

Croix de Guerre

Eight months after Stervinou mustered out of service, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre des Theatres d’Operations Exterieures with Silver Star, citation at the Ordre de la Division, for his engagements at Along Bay, his participation in the Weichow raid, and his role in accepting the Japanese surrender in Vietnam. He was individually cited for his “energy, courage and sang froid.”

Stervinou’s Citation for the Croix de Guerre, citing his energy,

courage and sang froid at Along bay, in the Weichow raid,

and in accepting the Japanese surrender in Vietnam.

After the War

The next year, Stervinou came to the United States. He earned a degree from the University of Houston, became a U.S. citizen in 1953, and for years directed Berlitz language institutes in the U.S. and Europe.

Widowed in 1978, Stervinou was re-married in 1981 to a U.S. Foreign Service Officer with USAID—Theodora (Teddy) Wood—who he met in Annandale, Virginia. The two spent years stationed in west Africa, working at USAID’s Regional Office in Abidjan where he promoted private sector development in central and west Africa at the height of the cold war.

After retiring in 1992, Stervinou continued working with French veterans organizations. In 2006, he was awarded France’ highest order of merit for military and civilian service, the Legion d’Honneur, at the level of Chevalier. In addition to the Legion d’Honneur and Croix de Guerre, over his military career he received the Croix de Combattant Volontaire, Medaille des Evades, Medaille de la Reconnaissance de la Nation, and Medaille d’Outre-Mere.

Stervinou (on right) during a ceremony when he was decorated with

the Legion d”Honneur for his military service by Ambassador

Levitte at the French Embassy in Washington, D.C., June 18, 2006.

In December 2017, in perfect health, Stervinou was walking one of the large Bouvier dogs that he and his wife Teddy were famous for. He slipped on an icy sidewalk in Washington, D.C., struck his head, and died of complications six months later at the age of 95. It was June 16, 2018—78 years, almost to the day—since he had heard de Gaulle exhort his countrymen to join the fight as Nazi Panzers rolled into Brest.

Epilogue

The military history of Lucien Corentin Stervinou is the history of special operations at the dawn of the modern age of irregular warfare. From 1940-1946, he was operationally engaged with every major American, British and French special operations force, from the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, precursor of today’s CIA; to the British Special Air Service, Special Operations Executive and Force 136; to France’s Central Bureau of Intelligence and Operations.

Stervinou’s extraordinary military career stands as a historical benchmark by which every special operations warrior who has followed can justly measure their own.

**********

The biographical material in this tribute is drawn mostly from Lucien Stervinou’s surviving writings and lecture notes, provided courtesy of Theodora Wood-Stervinou to whom special thanks are due. Without her assistance, the military history of this extraordinary special forces combatant could not have been written.

Jeff Goodson is a retired U.S. Foreign Service Officer. From 1983-2012, he worked on the ground in 49 countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East. He served 31 months in Afghanistan, including as USAID Chief of Staff (2006-2006) and Director of Development at ISAF HQ under General David Petraeus and General John Allen (2010-2012). Goodson worked with Lucien Stervinou at USAID’s Regional Office in Abidjan in the mid-1980s.